Trieste meets OpenAI Gym#

This notebook demonstrates how to use Trieste to apply Bayesian optimization to a problem that is slightly more practical than classical optimization benchmarks shown used in other tutorials. We will use OpenAI Gym, which is a popular toolkit for reinforcement learning (RL) algorithms.

Concretely, we are going to take the Lunar Lander environment, define a search space and describe it as an optimization problem, and use Trieste to find an optimal solution for the problem. And hopefully avoid too many landers crashing on the Moon surface along the way.

[1]:

import tensorflow as tf

import numpy as np

import trieste

import gpflow

import gym

env_name = "LunarLander-v2"

env = gym.make(env_name)

seed = 1793

np.random.seed(seed)

tf.random.set_seed(seed)

env.seed(seed)

/opt/hostedtoolcache/Python/3.7.15/x64/lib/python3.7/site-packages/gpflow/experimental/utils.py:43: UserWarning: You're calling gpflow.experimental.check_shapes.decorator.check_shapes which is considered *experimental*. Expect: breaking changes, poor documentation, and bugs.

f"You're calling {name} which is considered *experimental*."

/opt/hostedtoolcache/Python/3.7.15/x64/lib/python3.7/site-packages/gpflow/experimental/utils.py:43: UserWarning: You're calling gpflow.experimental.check_shapes.inheritance.inherit_check_shapes which is considered *experimental*. Expect: breaking changes, poor documentation, and bugs.

f"You're calling {name} which is considered *experimental*."

[1]:

[1793]

Introduction#

Let’s start by discussing the problem itself. In the Lunar Lander environment we are controlling a space module that needs to land on a Moon surface. The surface is piecewise linear and is generated randomly, but always has a flat landing pad in the middle (marked with flags on the renders). The module starts at the top with some random initial speed and direction. We are controlling three engines on the module: one on each side, and one at the bottom. At each step of the simulation we can choose to either fire one of the engines, or do nothing. The ultimate goal of the simulation is to land safely on the marked landing pad.

As usual in RL settings, the environment calculates reward points. Landing in the designated area gives the biggest reward, landing safely elsewhere is also rewarded but with less points. Crashing or flying off the screen results in big negative reward. Few points are also deducted along the way for firing up engines, thus motivating smaller usage of fuel. Additionally, to make the running time manageable, we are going to penalize simulations that take too long, by stopping them after a certain amount of steps and penalizing the reward.

Optimization problem#

Now let’s see how this task can be formulated as an optimization problem. We will be following an approach used by Turbo [EPG+19] and BOSH [MLR20] papers. The environment comes with a heuristic controller that makes decisions based on the current position and velocity of the module. This controller can be tuned by modifying 12 of its internal numerical parameters. These parameters form our optimization search space. The objective is the same as in the original RL setup: maximize the reward. Therefore we will be using Trieste to learn how to land the module safely on the designated pad, without taking too much time and wasting too much fuel.

The original code for the heuristic controller can be found in OpenAI Gym GitHub repo. Here is the parametrized version, taken from the repository of the Turbo paper:

[2]:

# controller code is copied verbatim from https://github.com/uber-research/TuRBO

# s is the state of the environment, an array of shape (1, 8)

# for details on its content see https://github.com/openai/gym/blob/master/gym/envs/box2d/lunar_lander.py

# w is the array of controller parameters, of shape (1, 12)

def heuristic_Controller(s, w):

angle_targ = s[0] * w[0] + s[2] * w[1]

if angle_targ > w[2]:

angle_targ = w[2]

if angle_targ < -w[2]:

angle_targ = -w[2]

hover_targ = w[3] * np.abs(s[0])

angle_todo = (angle_targ - s[4]) * w[4] - (s[5]) * w[5]

hover_todo = (hover_targ - s[1]) * w[6] - (s[3]) * w[7]

if s[6] or s[7]:

angle_todo = w[8]

hover_todo = -(s[3]) * w[9]

a = 0

if hover_todo > np.abs(angle_todo) and hover_todo > w[10]:

a = 2

elif angle_todo < -w[11]:

a = 3

elif angle_todo > +w[11]:

a = 1

return a

steps_limit = 1000

timeout_reward = -100

# this wrapper runs a single simulation of the landing

# for a given controller parameters values

# and computes the reward

# to keep running time reasonable simulation is stopped after `steps_limit` steps

def demo_heuristic_lander(env, w, print_reward=False):

total_reward = 0

steps = 0

s = env.reset()

while True:

if steps > steps_limit:

total_reward -= timeout_reward

break

a = heuristic_Controller(s, w)

s, r, done, info = env.step(a)

total_reward += r

steps += 1

if done:

break

if print_reward:

print(f"Total reward: {total_reward}")

return total_reward

In the original OpenAI Gym Lunar Lander code controller parameters have fixed values. The smallest parameter is set to 0.05, and the biggest parameter value is 1.0. Thus we will set the search range for each parameter to be the same from 0.0 to 1.2.

[3]:

search_space = trieste.space.Box([0.0] * 12, [1.2] * 12)

Let’s see what kind of reward we might get by just using random parameters from this search space. Usual reward values for the Lunar Lander environment are between -250 (terrible crash) to 250 (excellent landing).

[4]:

for _ in range(10):

sample_w = search_space.sample(1).numpy()[0]

demo_heuristic_lander(env, sample_w, print_reward=True)

Total reward: -153.23779126561908

Total reward: -130.66175273798774

Total reward: -4.608495153386542

Total reward: -109.79312691900881

Total reward: -154.12358650679934

Total reward: 7.776986853330797

Total reward: -70.21037893264943

Total reward: -159.89749689038592

Total reward: -132.46077863019033

Total reward: -164.63629464381404

As you can see, most of the random sets of parameters result in a negative reward. So picking a value from this search space at random can result in a various unwanted behaviors. Here we show some examples of the landing not going according to plan. Each of these examples was created with a sample of the parameter values from the search space.

Warning: all the videos in this notebook were pre-generated. Creating renders of OpenAI Gym environments requires various dependencies depending on software setups and operating systems, so we have chosen not to do it here in the interest of transferability of this notebook. For those interested in reproducing these videos, we have saved the input parameters and the code we used to generate them in the Trieste repository, in the folder next to this notebook. However because of the stochastic nature of the environment and the optimization described here, your results might differ slightly from those shown here.

[5]:

import io

import base64

from IPython.display import HTML

def load_video(filename):

video = io.open("./lunar_lander_videos/" + filename, "r+b").read()

encoded = base64.b64encode(video)

return HTML(

data="""

<video width="360" height="auto" alt="test" controls>

<source src="data:video/mp4;base64,{0}" type="video/mp4" />

</video>""".format(

encoded.decode("ascii")

)

)

Slamming on the surface#

This is a very common failure mode in this environment - going too fast and slamming on the surface.

[9]:

load_video("slam.mp4")

[9]:

Since the reward is stochastic, our goal is to maximize its expectation (or rather here minimize its negated expectation since Trieste only deals with minimization problems). To decrease the observation noise, our observer returns the average of the reward over 10 runs.

[10]:

N_RUNS = 10

def lander_objective(x):

# for each point compute average reward over n_runs runs

all_rewards = []

for w in x.numpy():

rewards = [demo_heuristic_lander(env, w) for _ in range(N_RUNS)]

all_rewards.append(rewards)

rewards_tensor = tf.convert_to_tensor(all_rewards, dtype=tf.float64)

# triste minimizes, and we want to maximize

return -1 * tf.reshape(tf.math.reduce_mean(rewards_tensor, axis=1), (-1, 1))

observer = trieste.objectives.utils.mk_observer(lander_objective)

Solving the optimization problem with Trieste#

Here we do normal steps required to solve an optimization problem with Trieste: generate some initial data, create a surrogate model, define an acquisition funciton and rule, and run the optimization. Optimization step may take a few minutes to complete.

We are using standard Gaussian Process with an RBF kernel, and Augmented Expected Improvement [HANZ06] as an acquisition function that can handle higher noise.

[11]:

num_initial_points = 2 * search_space.dimension

initial_query_points = search_space.sample(num_initial_points)

initial_data = observer(initial_query_points)

[12]:

def build_model(data):

variance = tf.math.reduce_variance(data.observations)

kernel = gpflow.kernels.RBF(variance=variance)

gpr = gpflow.models.GPR(data.astuple(), kernel)

gpflow.set_trainable(gpr.likelihood, False)

# Since we are running multiple simulations per observation,

# it is possible to account for variations in observation noise

# by using a different likelihood variance for each observation.

# This is possible to model with VGP, as described here:

# https://gpflow.readthedocs.io/en/master/notebooks/advanced/varying_noise.html\

# In the interest of brevity we have chosen not to do it in this notebook.

return trieste.models.gpflow.GaussianProcessRegression(gpr)

model = build_model(initial_data)

/opt/hostedtoolcache/Python/3.7.15/x64/lib/python3.7/site-packages/gpflow/experimental/utils.py:43: UserWarning: You're calling gpflow.experimental.check_shapes.checker.ShapeChecker.__init__ which is considered *experimental*. Expect: breaking changes, poor documentation, and bugs.

f"You're calling {name} which is considered *experimental*."

[13]:

acq_fn = trieste.acquisition.function.AugmentedExpectedImprovement()

rule = trieste.acquisition.rule.EfficientGlobalOptimization(acq_fn) # type: ignore

[14]:

N_OPTIMIZATION_STEPS = 200

bo = trieste.bayesian_optimizer.BayesianOptimizer(observer, search_space)

result = bo.optimize(

N_OPTIMIZATION_STEPS, initial_data, model, rule

).final_result.unwrap()

Optimization completed without errors

Analyzing the results#

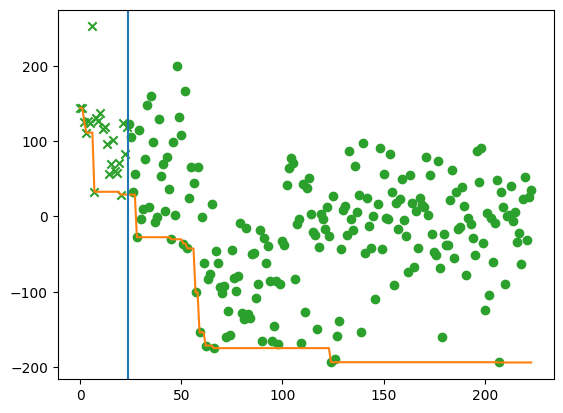

First, let’s just plot observations of the expected reward, to ensure Trieste indeed found a better configuration of the controller. Remember that we flipped the sign of the reward.

[15]:

from trieste.experimental import plotting

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

ax = plt.gca()

plotting.plot_regret(

result.dataset.observations.numpy(), ax, num_init=len(initial_data)

)

Here we choose the query point that gives the best predictive expected reward according to our model. When running the simulation with at this point, we expect to see mostly large positive rewards.

[16]:

mean = result.model.predict(result.dataset.query_points)[0]

w_best = result.dataset.query_points[np.argmin(mean), :]

for _ in range(10):

demo_heuristic_lander(env, w_best.numpy(), print_reward=True)

Total reward: 1.995386171988443

Total reward: 248.59766707026404

Total reward: 286.40132144157354

Total reward: 275.56896987977336

Total reward: 12.253378635630924

Total reward: 261.7622373875663

Total reward: 196.2255768915281

Total reward: 26.524629671925382

Total reward: 21.65147885120038

Total reward: 24.74879345480467

Finally, let’s have a look at what the good controller configuration looks like in action.

Warning: as mentioned above, this video was also pre-generated.

[17]:

load_video("success.mp4")

[17]:

[ ]: